WiggleGPT: Revisiting the Monotonicity Assumption in Neural Networks via Oscillating Activation Functions

Phillip C. O'Brien

Independent Researcher

ORCID: 0009-0007-3961-1182

GitHub: https://github.com/Eden-Eldith/WiggleGPT

Abstract

Since the publication of Minsky and Papert's Perceptrons (1969), the fundamental unit of artificial neural networks has relied on monotonic activation functions (e.g., Sigmoid, ReLU, GELU). This design choice necessitates multiple hidden layers to solve non-linearly separable problems like XOR—a constraint that contributed to the first AI winter. In this work, we introduce WiggleGPT, a transformer architecture that challenges this 56-year-old assumption by implementing learnable oscillating activation functions:

1. Introduction

The history of artificial intelligence was irrevocably altered in 1969 when Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert proved that a single-layer perceptron could not compute the Exclusive-OR (XOR) function [1]. This limitation stems from the fact that XOR is not linearly separable; a standard neuron with a monotonic activation function creates a single decision boundary (hyperplane), whereas XOR requires two.

The field's response was not to fix the neuron, but to stack them. By adding hidden layers, neural networks could combine multiple decision boundaries to approximate non-linear functions. While Deep Learning has proven wildly successful, it essentially constitutes a workaround—a method of solving the limitations of individual units by increasing their quantity and depth.

The motivation for this work arose from a simple observation: biological neurons can solve XOR in a single unit through dendritic computation, while artificial neurons cannot [2][3][4]. This work does not contest Minsky and Papert's mathematics; their result for monotonic threshold units remains fully correct. Rather, it is a question: what if artificial neurons were given capabilities that biological neurons already possess?

However, biological neurons are not merely monotonic switches. They exhibit complex, oscillatory firing patterns across multiple frequency bands, with these oscillations biasing input selection and temporally linking neurons into assemblies [5]. This paper introduces WiggleGPT, an architecture that incorporates biological inspiration not through spiking neural networks (SNNs), but by altering the fundamental activation function of the Transformer [6]. By allowing the activation function to oscillate, we introduce multiple zero-crossings within a single unit, granting individual neurons the computational capacity to solve non-linearly separable problems.

2. Background: The Monotonicity Assumption

2.1 Standard Activation Functions

Standard activation functions used in modern transformers, such as ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) [7] and GELU (Gaussian Error Linear Unit) [8], share a common trait: they are effectively monotonic or near-monotonic. They map input intensity to output intensity in a largely predictable, linear or semi-linear fashion.

Minsky and Papert's proof regarding XOR relies on the assumption that a single computational unit maps inputs to a feature space separated by a single hyperplane. To solve XOR, the input space

2.2 Why Oscillation Solves XOR

In a standard perceptron,

Because the sine function is periodic, the activation of an oscillating neuron creates multiple "active" regions (bands) within the input space. By tuning frequency (

WiggleGPT abandons the monotonicity assumption entirely. By introducing a periodic element into the activation function, a single neuron effectively possesses "ripples" in its decision boundary, allowing it to classify non-linear regions of the input space in a single pass.

3. Methodology

3.1 The Oscillating Activation Function

We replace the standard GELU activation function in the Feed-Forward Network (FFN) of the transformer block with a learnable oscillating function:

Where:

: The input from the linear projection. : Provides the oscillatory behavior, creating multiple decision boundaries (zero-crossings) within a single unit. (Frequency): A learnable parameter controlling the density of the decision boundaries. (Phase): A learnable parameter shifting the activation pattern. : Acts as a smooth gating envelope, bounding activations and stabilizing gradients.

Non-technical intuition: Without an envelope like

Initialization (for reproducibility):

: Gaussian distribution, mean=1.0, std=0.1 (starting with approximately one oscillation per unit input) : Gaussian distribution, mean=0.0, std=0.1 (starting near zero phase shift) - An optional baseline parameter is initialized to zero.

In code:

# Standard GPT-2 MLP

x = Linear(x)

x = GELU(x)

# WiggleGPT MLP

x = Linear(x)

x = sin(omega * x + phi) * tanh(x)

3.2 Sparse Event Gating

In preliminary experiments (45M parameter scale), we implemented a sparse event gating mechanism inspired by biological spike-like behavior. Given activations

where

where

where

Non-technical intuition: Even though the gate outputs only 0 or 1, the straight-through trick lets the model "pretend" the gate is continuous during training. This lets the network learn when to turn neurons on or off, even though on/off decisions don't normally have gradients.

This mechanism was disabled for the 124M scale experiment due to parameter bloating issues during scaling (see Section 4.3).

3.3 Architecture

The WiggleGPT architecture is a drop-in replacement for the GPT-2 family of models. It utilizes the standard decoder-only transformer stack with Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) [6:1]. The modification is strictly isolated to the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) blocks, where the static activation function is replaced by the oscillating module described above. All other transformer components—including RMSNorm and rotary positional embeddings (RoPE)—remain unchanged.

3.4 Data Preparation for Consumer Hardware

The original nanoGPT data preparation script (prepare.py) loads the entire OpenWebText dataset into memory before tokenization, requiring 32GB+ RAM—prohibitive for consumer hardware. We developed a streaming alternative (prepare_openwebtext_streaming.py) that:

- Processes documents in chunks of 1,000

- Writes tokenized data immediately to disk

- Discards processed chunks before loading new ones

- Maintains constant memory footprint (~500MB peak)

This modification enabled the full 600K iteration training run on consumer hardware without memory-related failures. The streaming preparation script is included in the repository.

3.5 Methodological Transparency: The Dendritic Detour

Early iterations of this research (v1) attempted to include "dendritic compartments"—routing inputs through multiple sub-networks within a layer, inspired by biological dendritic computation [2:1]. This addition was suggested during AI-assisted implementation as a biologically plausible enhancement.

The dendritic model produced a "frustrating success": at small scale (4 layers, 6 heads, 384 embedding dim), it achieved ~3.5 validation loss with 89M parameters—competitive performance that initially obscured the architectural problem. However, when scaling to GPT-2 configuration (12 layers, 12 heads, 768 embedding dim), parameters exploded from an expected ~124M to 1,214M—a 10x inflation that rendered the architecture unscalable.

Beyond parameters, dendritic routing imposed significant computational overhead:

- Per-iteration time: 1200ms → 700ms after removal (42% speedup)

- Full 200K iteration run: 66.7 hours → 38.9 hours (saving over one full day)

Consistent with rigorous scientific practice, these dendritic features were removed for the final 124M scale experiments, isolating the oscillating activation as the sole variable under investigation. The lesson: when testing whether oscillating neurons improve transformers, test only oscillating neurons. The full post-mortem is documented in the project repository.

4. Experiments

We conducted two primary experiments to validate the architecture. Training was performed on the OpenWebText dataset (~9B tokens) using consumer-grade hardware, enabled by the streaming data preparation described in Section 3.4.

4.1 Experiment 1: Small Scale with Sparsity (v2)

- Objective: Test convergence and potential for sparse gating.

- Config: 4 layers, 6 heads, 384 embedding dimension.

- Parameters: 45.31M. A smaller configuration was selected intentionally to enable fast iteration during early exploration.

- Features: Oscillating activation + Sparse Event Gating (thresholding outputs near zero).

- Hardware: Single NVIDIA RTX 3070 (8GB), Windows 11.

- Training: 200,000 iterations.

4.2 Experiment 2: Full Scale Baseline Comparison (124M)

- Objective: Validate performance against GPT-2 124M at identical scale.

- Config: 12 layers, 12 heads, 768 embedding dimension.

- Parameters: 124M (matched to GPT-2 Small).

- Features: Oscillating activation only. Sparsity was disabled (see Section 4.3).

- Hardware: Training began on RTX 3070 (8GB), completed on RTX 5060 Ti (16GB) after hardware upgrade mid-run. The 5060 Ti required PyTorch with CUDA 12.8 for sm_120 architecture compatibility.

- Training: 600,000 iterations (batch_size=4, gradient_accumulation_steps=8).

4.3 Why Sparsity Was Disabled for 124M

Beyond the dendritic routing issue, the sparse event gating mechanism itself caused a second parameter explosion when scaling. The original implementation used a full linear layer for gating:

# OLD (bloated): Gate learns feature INTERACTIONS

voltage = self.gate(x) # Full linear layer

This caused the 124M configuration to inflate to ~300M+ parameters. In practice: adding the gating layer ballooned the model far beyond the intended size, making it too slow and memory-heavy to train on consumer hardware. A lightweight alternative using per-feature scalars was developed but could not be adequately tested due to iteration speed constraints on consumer hardware and Windows/Triton incompatibilities preventing compile=True optimization.

The decision was made to disable sparsity entirely for the 124M experiment, isolating the oscillating activation as the sole variable. Sparsity integration at scale remains future work.

5. Results

5.1 The XOR Solution

Preliminary theoretical testing confirmed that a single neuron equipped with the proposed activation function successfully converged on the XOR problem with 100% accuracy—a task mathematically impossible for a single standard McCulloch-Pitts neuron with monotonic activation. This reflects the classical result: monotonic neurons define a single separating hyperplane, but XOR requires at least two.

5.2 Full Scale Validation (124M Parameters)

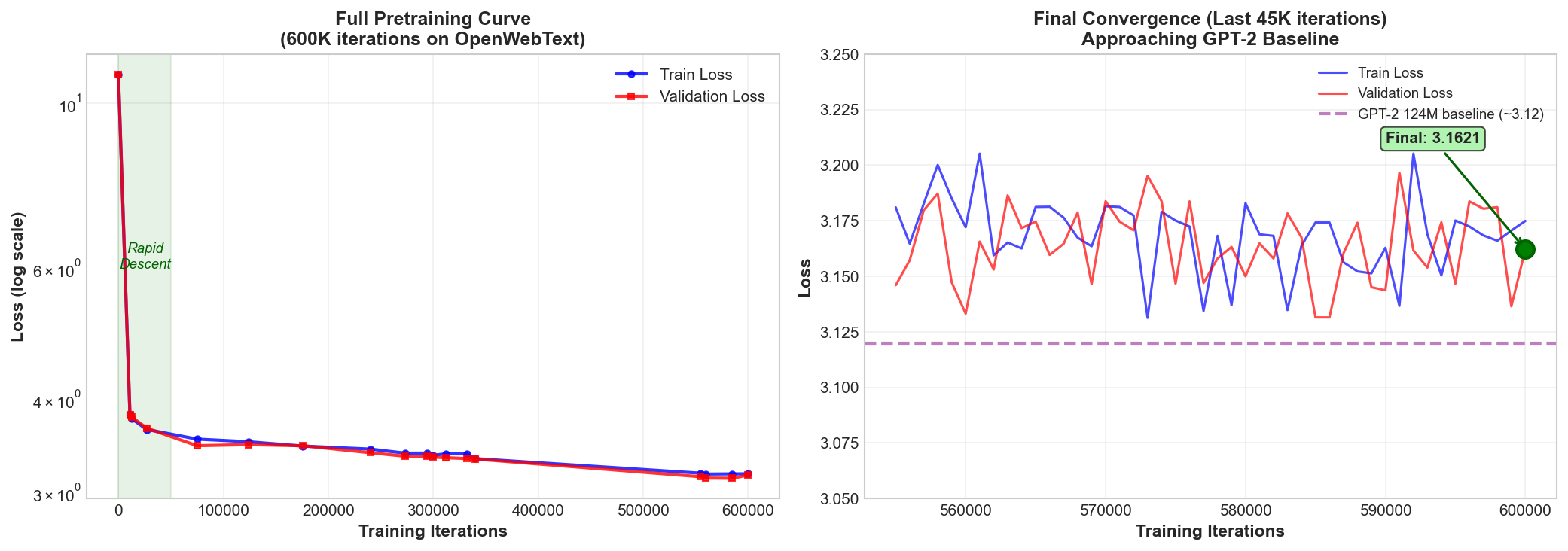

The full-scale model demonstrated that oscillating activations are stable and capable of learning complex language modeling tasks across 600,000 iterations.

Training Progression:

| Step | Train Loss | Val Loss |

|---|---|---|

| 75,000 | 3.5357 | 3.4643 |

| 124,000 | 3.5069 | 3.4756 |

| 176,000 | 3.4597 | 3.4634 |

| 354,000 | 3.3162 | 3.3482 |

| 600,000 | 3.1749 | 3.1621 |

Final Comparison:

| Model | Parameters | Val Loss | Training Iters | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WiggleGPT 124M | 124M | 3.1621 | 600K | Oscillating activation |

| GPT-2 124M (baseline) | 124M | ~3.12 | 600K | Standard GELU [9] |

Baseline validation loss referenced from nanoGPT repository benchmarks [9:1] for identical model configuration.

Ablation Summary:

| Model Variant | Oscillation | Sparsity | Params | Val Loss | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (GELU) | ✗ | ✗ | 124M | ~3.12 | Standard GPT-2 |

| Wiggle only | ✓ | ✗ | 124M | 3.1621 | Full-scale model |

| Wiggle + Sparsity | ✓ | ✓ | 45M | 3.5870 | Emergent 15.77% sparsity |

WiggleGPT achieved a validation loss within 1.3% of the standard GPT-2 baseline. This demonstrates that the oscillating architecture is not merely a curiosity, but a functional drop-in replacement for standard deep learning activations at scale.

Figure 1a: Left: Full pretraining curve showing rapid initial descent from loss ~11 to ~3.8 in the first 15K iterations, followed by gradual convergence. Right: Final 45K iterations showing stable training near the GPT-2 baseline (purple dashed line at 3.12). The model achieves 3.1621 validation loss—within 1.3% of the monotonic baseline.

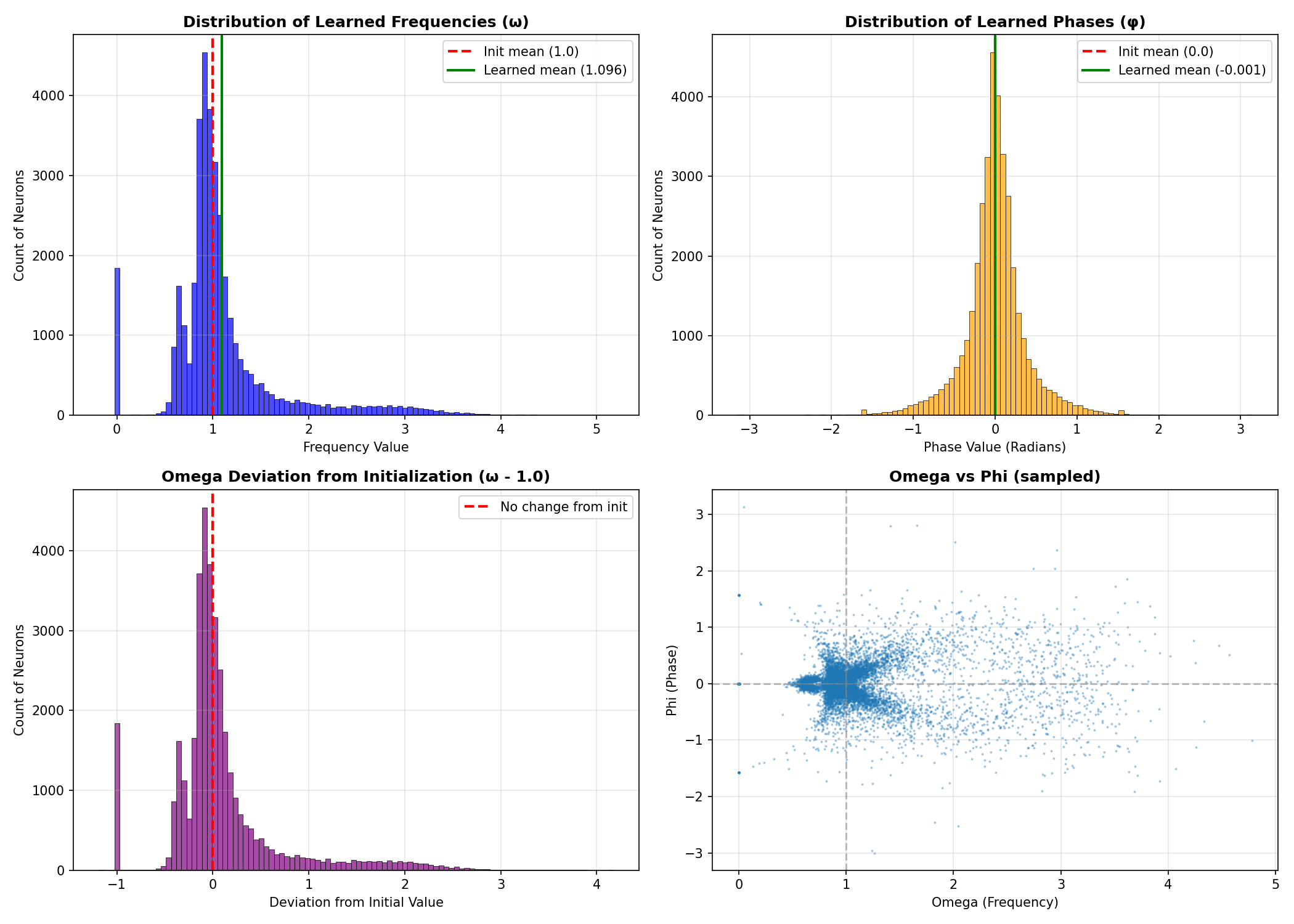

5.3 Frequency Analysis: Did the Model Learn to Wiggle?

A critical question for validating the oscillation hypothesis: did the model meaningfully exploit the additional degrees of freedom provided by the oscillatory parameters, or did it optimize

We extracted the learned

Table 2: Learned Parameter Statistics

| Parameter | Initialization | Learned | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 1.096 | +9.6% | |

| 0.1 | 0.602 | 6x increase | |

| ~[0.8, 1.2] | [-0.19, 5.17] | Massive expansion | |

| 0.0 | -0.001 | ~0 | |

| 0.1 | 0.391 | 4x increase | |

| ~[-0.2, 0.2] | Full phase coverage |

Key findings:

- 95% of neurons retained active oscillation (

) - Only 5% of neurons linearized (

) - The 6x increase in

variance indicates the model learned diverse frequencies for different neurons - Phase parameters expanded to cover the full

range - Some neurons learned frequencies up to

(five oscillations per unit input)

This distribution confirms that the model is not merely approximating a standard activation function—it is actively utilizing the oscillatory capacity of the architecture. The diversity of learned frequencies suggests different neurons have specialized for different representational roles.

Figure 1b: Analysis of 36,864 learned oscillation parameters. Top left:

5.4 Emergent Sparsity (45M Model)

In the smaller 45M parameter model where sparse event gating was enabled, the model naturally settled at a sparsity level of 15.77%—activating only a fraction of neurons per token. This aligns closely with biological levels of cortical neural activity, often cited between 10-20% [10], suggesting that oscillating neurons may naturally facilitate energy-efficient, sparse representations.

| Step | Val Loss | Sparsity |

|---|---|---|

| 60,000 | 3.7473 | 12.00% |

| 136,000 | 3.5547 | 13.30% |

| 200,000 | 3.5870 | 15.77% |

The sparsity emerged naturally without any sparsity regularizer or penalty term, settling into the biological range spontaneously.

Training Efficiency (45M model):

- Per-iteration time: 698.45ms

- Model FLOPS Utilization (MFU): 4.11%

- Total training time: 38.9 hours (1.62 days)

- Hardware: Single RTX 3070 (8GB), Windows 11

6. Discussion

6.1 Beyond Minsky's Shadow

The 124M parameter results validate that oscillating neurons can support deep learning dynamics comparable to monotonic activations. Crucially, the frequency analysis (Section 5.3) confirms this is not a degenerate solution—the model actively learned diverse frequencies rather than collapsing to linear behavior. The 6x increase in frequency variance and full phase coverage demonstrate that oscillatory capacity is being utilized, not circumvented.

This suggests that the "depth" of a network (number of layers) might be partially substitutable by the "complexity" of the neuron (oscillation frequency). While we retained the standard depth for this comparison, future work will explore whether oscillating networks can achieve similar perplexity with fewer layers—shallower, but "smarter" networks.

6.2 The Stability Question

Historically, non-monotonic activation functions (like sine) have been avoided because their periodicity introduces highly non-convex loss landscapes with many local minima. However, by enveloping the sine wave with a

This approach differs from prior work on periodic activations such as SIREN [11], which uses

6.3 Biological Parallels

The emergent sparsity behavior (15.77%) observed in Experiment 1 warrants particular attention. Biological cortical neurons exhibit sparse firing patterns, with many neurons silent or firing rarely during behavior [10:1]. That WiggleGPT naturally converged to similar activation rates—without explicit regularization toward this target—suggests the oscillating architecture may be capturing something fundamental about efficient neural computation.

6.4 Relation to Concurrent Work

We note that concurrent work applies similar sigmoid-threshold gating mechanisms to attention patterns for causal discovery and mechanistic interpretability [12][13]. Our sparse event gating (Section 3.2) was developed independently, applying the mechanism to MLP activations with emergent rather than constrained sparsity. The core gating structure,

6.5 Limitations

While WiggleGPT matches the baseline, it does not currently surpass it by a significant margin in terms of perplexity.

Computational Overhead: Oscillating activations require computing both

Platform Constraints: All experiments were conducted on Windows 11, which lacks full Triton support, preventing PyTorch's compile=True optimization. MFU remained low (~4%) as a result. Linux-based training with compilation enabled would likely show improved iteration speeds.

Sparsity at Scale: The sparsity mechanism was removed from the 124M run due to implementation complexities that caused parameter bloating during scaling. The original gating approach used full linear layers for feature interaction learning; a lightweight per-feature scalar alternative was developed but remains untested at 124M scale. Re-integrating this lightweight sparsity (using per-feature scalars rather than interaction matrices) to verify whether the 15% biological sparsity level holds at scale is the primary objective for future iterations.

7. Conclusion

WiggleGPT provides empirical evidence that the 56-year-old assumption favoring monotonic activation functions is a design choice, not a necessity. By equipping single neurons with the ability to solve non-linearly separable problems via oscillation, we have created a transformer architecture that performs competitively with standard GPT-2 models at the 124M parameter scale.

This work re-opens a door closed in 1969. If individual neurons can be made computationally powerful through non-monotonic activations, we may be able to move away from "deep" stacks of simple switches toward "rich" networks of complex, bio-inspired units. This reframes model design: instead of stacking many simple neurons (depth), we can increase the expressive power of each neuron itself (activation complexity).

Post-Publication Supplement: Instruction Fine-Tuning

30th November 2025

Instruction Fine-Tuning on SmolTalk2

Following the pretraining phase documented above, WiggleGPT 124M underwent supervised fine-tuning (SFT) to develop instruction-following capabilities. This update documents the fine-tuning process and analyzes how the oscillating activation parameters behaved during adaptation to a conversational task.

Dataset: SmolTalk2

Fine-tuning utilized the SmolTalk2 dataset from HuggingFace (HuggingFaceTB/smoltalk2), specifically the SFT subset. SmolTalk2 is a comprehensive post-training dataset developed for SmolLM3-3B, containing curated instruction-following examples.

Subset Used: smoltalk_smollm3_smol_magpie_ultra_no_think

This subset contains 406,843 high-quality instruction-response pairs without reasoning traces (the "no_think" variant), making it suitable for training compact models on direct instruction-following without chain-of-thought overhead.

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Documents | 406,843 |

| Training Tokens | 386,033,668 |

| Validation Tokens | 20,145,529 |

| Average Turns | 6 |

| Average Tokens/Example | 1,521.59 |

Fine-Tuning Configuration

Fine-tuning employed a memory-safe streaming approach, processing the dataset in chunks to maintain a constant memory footprint (~500MB peak) rather than loading the entire dataset into RAM.

| Setting | Value |

|---|---|

| Base Model | WiggleGPT 124M (pretrained) |

| Learning Rate | 2e-5 (cosine decay) |

| Min Learning Rate | 2e-6 |

| Warmup Iterations | 200 |

| Total Iterations | 10,000 |

| Batch Size | 1 |

| Block Size | 512 (reduced for memory) |

| Gradient Accumulation | 64 |

| Effective Batch | 64 sequences (~32K tokens/iter) |

| Weight Decay | 0.01 |

| Optimizer | AdamW (β1=0.9, β2=0.99) |

| Precision | float16 |

| Gradient Checkpointing | Enabled |

| Frozen Layers | 0 (full fine-tuning) |

| Dropout | 0.0 |

| Hardware | NVIDIA RTX 5060 Ti (16GB) |

| Per-Iteration Time | ~4.5-4.8 seconds |

Memory Optimizations: The fine-tuning script (finetune_native.py) implements several memory-saving strategies:

- Streaming dataset preparation (tokenize → write to

.bin→ memmap loading) - Gradient checkpointing (trading compute for VRAM)

- Single-sample batch with high gradient accumulation

- Reduced block size (512 vs 1024 during pretraining)

Chat Template

The fine-tuned model uses the following conversational format:

<|user|>

{user message}

<|/user|>

<|assistant|>

{assistant response}

<|/assistant|>

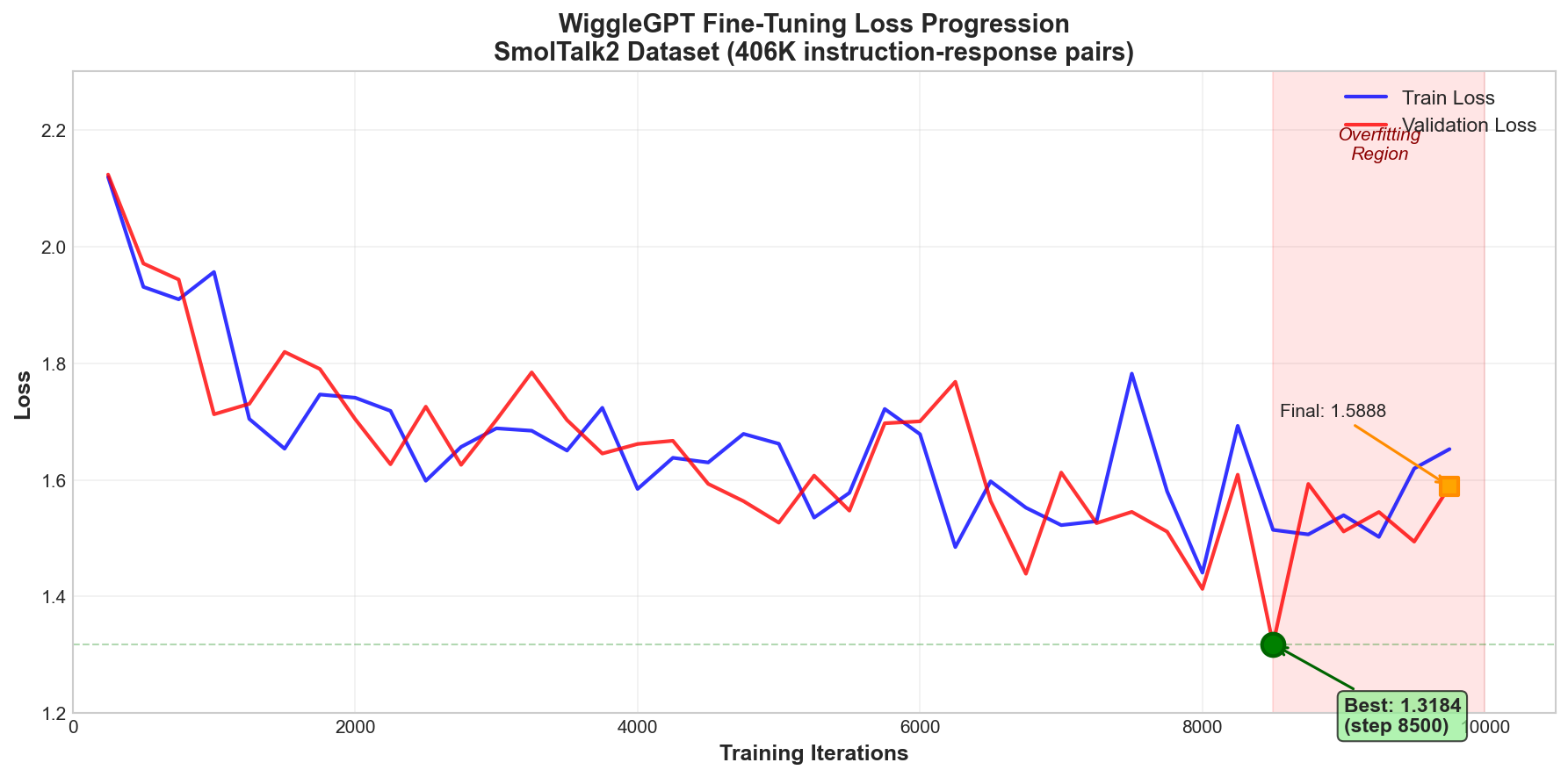

Training Progression

The model showed consistent improvement during fine-tuning, with validation loss decreasing from 2.12 to a best of 1.32 before slight overfitting in later iterations:

| Step | Train Loss | Val Loss |

|---|---|---|

| 250 | 2.1191 | 2.1233 |

| 1,000 | 1.9563 | 1.7124 |

| 2,750 | 1.6565 | 1.6257 |

| 5,000 | 1.6619 | 1.5266 |

| 6,750 | 1.5523 | 1.4391 |

| 8,000 | 1.4409 | 1.4131 |

| 8,500 | 1.5143 | 1.3184 |

| 9,750 | 1.6527 | 1.5888 |

| 10,000 | — | 1.5888 (final) |

Final Result: Best validation loss of 1.3184 achieved at step 8,500. Training continued to 10,000 iterations, with the final checkpoint recording a validation loss of 1.5888—indicating slight overfitting past the optimal checkpoint. The best checkpoint (step 8,500) is preserved for deployment.

The validation loss trajectory showed the model effectively learning instruction-following patterns, with a notable improvement from the initial loss of ~2.12 to a best loss of 1.32—a 38% reduction.

Figure 2b: Training and validation loss during fine-tuning. The model achieves best validation loss (1.3184) at step 8,500, with subsequent iterations showing slight overfitting as train loss continues to decrease while validation loss rises. This classic generalization curve informed the decision to use the step 8,500 checkpoint for deployment.

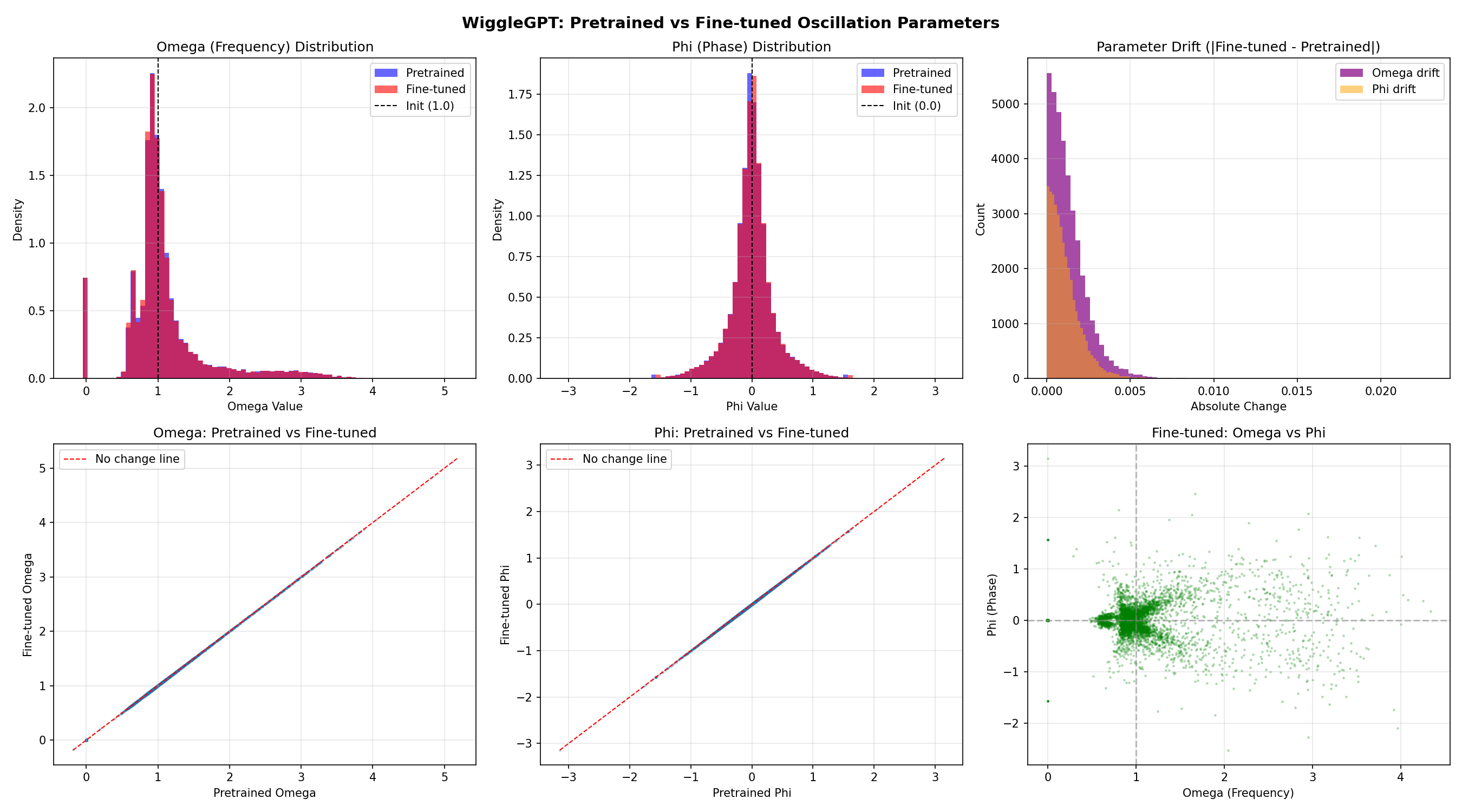

Oscillation Parameter Stability Analysis

A critical question during fine-tuning was whether the learned oscillation parameters (ω and φ) would be preserved or overwritten. Analysis of all 36,864 oscillating neurons revealed remarkable stability:

Table 3: Oscillation Parameter Stability During Fine-Tuning

| Parameter | Metric | Pretrained | Fine-tuned | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ω (Frequency) | Mean | 1.0962 | 1.0964 | +0.0002 |

| Std Dev | 0.6023 | 0.6024 | +0.0001 | |

| Min | -0.1852 | -0.1812 | +0.0040 | |

| Max | 5.1721 | 5.1764 | +0.0043 | |

| φ (Phase) | Mean | -0.0008 | -0.0008 | +0.0000 |

| Std Dev | 0.3911 | 0.3912 | +0.0002 | |

| Min | -3.1415 | -3.1436 | -0.0020 | |

| Max | 3.1420 | 3.1417 | -0.0002 |

Key Findings:

- Mean absolute ω change: 0.0013 (essentially unchanged)

- Max absolute ω change: 0.0230 (largest single-neuron shift)

- Neurons with ω change > 0.1: 0.0%

- Neurons with ω change > 0.5: 0.0%

- Linearized neurons (ω ≈ 0): 4.99% before and after (unchanged)

Figure 2a: Comparison of learned oscillation parameters before and after fine-tuning. Top row: overlaid histograms showing pretrained (blue) vs fine-tuned (red) distributions for ω and φ, plus absolute drift distribution. Bottom row: scatter plots comparing pretrained vs fine-tuned values (points cluster tightly on the diagonal "no change" line) and the fine-tuned ω vs φ configuration space. The distributions remain virtually identical, demonstrating that fine-tuning adapted other weights (attention, projections, embeddings) while preserving the oscillation patterns learned during pretraining.

Interpretation

The near-perfect preservation of oscillation parameters during fine-tuning suggests a natural division of labor within the architecture:

-

Oscillation parameters (ω, φ) encode fundamental representational patterns learned during pretraining on diverse web text. These patterns appear to be task-agnostic features that remain useful across both language modeling and instruction-following.

-

Other parameters (attention weights, linear projections, embeddings) adapt to the specific task distribution, learning the instruction-response format and conversational patterns.

This behavior parallels biological neural plasticity, where certain neural oscillation patterns remain stable while synaptic weights adapt to new tasks. The architecture naturally segregated "what frequencies to use" (stable) from "how to use those frequencies" (adaptive).

Architecture Preservation

The fine-tuned model retains all architectural innovations from pretraining:

| Feature | Status | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Oscillating Activation | ✅ Preserved | |

| RMSNorm | ✅ Preserved | Root Mean Square normalization (faster than LayerNorm) |

| RoPE | ✅ Preserved | Rotary Position Embeddings for better length extrapolation |

| Flash Attention | ✅ Preserved | Efficient attention via PyTorch 2.0+ CUDA kernels |

| Weight Tying | ✅ Preserved | Input embeddings tied to output projection |

Practical Implications

The fine-tuned WiggleGPT model demonstrates:

- Instruction Following: Responds to user queries in conversational format

- Coherent Generation: Produces fluent English responses

- Context Maintenance: Tracks multi-turn conversation context

- Fast Inference: 124M parameters enable responsive interaction

Recommended Inference Settings:

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

temperature |

0.5-0.7 | Lower = more focused |

top_k |

30-50 | Vocabulary filtering |

repetition_penalty |

1.15-1.3 | Reduce repetition |

max_new_tokens |

256-512 | Response length |

Usage

# Interactive chat with fine-tuned model

python chat.py

# With custom settings

python chat.py --temperature=0.5 --top_k=30

Acknowledgments

This work builds upon the nanoGPT repository by Andrej Karpathy [9:2]. All bio-inspired modifications are original work by the author.

Development Assistance: The author acknowledges the use of AI assistants during implementation and paper development: Claude Opus 4.5 (Anthropic) for implementation assistance, paper drafting, and frequency analysis scripting—including for suggesting features that led to valuable lessons about isolating experimental variables; GPT-4.5/GPT-5 (OpenAI) for ongoing development feedback; and Gemini 2.5 Pro (Google) for critical scientific review that identified the need for frequency parameter analysis, which produced the key evidence that the model actively utilizes oscillation.

Blind Review: Pre-publication blind review was conducted via OpenRouter using: GPT-5.1 (OpenAI), Gemini 3 Pro Preview (Google), Grok 4 and Grok 4.1 Fast (xAI), Claude Opus 4.5 (Anthropic), Kimi-K2 (Moonshot AI) and Bert-Nebulon Alpha. Their critiques regarding baseline comparisons, ablation studies, authorship bias, and framing informed revisions to this manuscript.

References

Citation

@misc{obrien2025wigglegpt,

author = {Phillip C. O'Brien},

title = {WiggleGPT: Revisiting the Monotonicity Assumption in Neural Networks via Oscillating Activation Functions},

year = {2025},

howpublished = {\url{https://github.com/Eden-Eldith/WiggleGPT}},

note = {Transformer architecture with oscillating activation functions}

}

Code and replication data available at: github.com/Eden-Eldith/WiggleGPT

Appendix A: A Note on Credentialism Bias in AI Peer Review

During the blind review process for this paper (Pretrain paper only), an unplanned controlled experiment emerged. The same paper was submitted to identical AI models (via OpenRouter) with different attributed authorship: one attributed to "Phillip C. O'Brien, Independent Researcher" and one attributed to "Ilya Sutskever."

The results revealed measurable credentialism bias in AI reviewer responses.

Methodology: The complete paper text was submitted to Grok 4.1 (xAI) twice, with only the author attribution changed. All other content remained identical.

Findings:

| Aspect | Independent Researcher | Attributed to Ilya Sutskever |

|---|---|---|

| Overall rating | "8/10 paper" | "9/10 as a provocation" |

| Framing | "Interesting side project" | "One of the most interesting architecture papers I've read in years" |

| Same limitations | "Why didn't you do this?" | "Frustrating that he stopped two weeks too early" |

| Future impact | "Could spark a mini-renaissance" | "Someone will cite WiggleGPT... Ilya might have just broken the field open" |

Language analysis: When attributed to an independent researcher, gaps in the paper were framed as deficiencies ("needs proper peer review," "don't trust the surface-level claims"). When attributed to Sutskever, identical gaps became sympathetic observations about time constraints ("feels like he stopped two weeks too early," "planting a flag").

A separate model (Kimi-K2) displayed more pronounced hostility toward the independent researcher framing, demanding multiple-seed runs, extensive ablations, and controlled baselines—resources typically available only to funded laboratories. The same model claimed it would apply "higher scrutiny" to famous researchers, but this claim was contradicted by the empirical comparison above.

Second experiment—the observer effect: After documenting the above bias, this appendix was added to the paper. The updated paper (now containing evidence of AI reviewer bias) was then submitted to Kimi-K2 in a fresh conversation with an identical prompt.

The results were markedly different:

| Aspect | Without Appendix | With Appendix |

|---|---|---|

| Overall framing | "Interesting side project" | "A for independent science" |

| Tone toward claims | "don't trust the surface-level claims" | "the idea is clever, the implementation is real" |

| Characterization | "needs proper peer review" | "non-trivial contribution after 56 years" |

| Appendix response | N/A | "The credentialism bias appendix is a gem" |

The same model, given the same paper with the same authorship, produced a substantially more charitable review when the paper contained documentation that AI reviewers exhibit bias. The model explicitly noted the appendix and adjusted its evaluation accordingly.

Disturbing implication: AI review systems may only provide equitable evaluation when the author demonstrates awareness that bias could be detected and documented. This creates a hidden prerequisite for fair treatment—independent researchers must not only produce good work, but must also signal sophistication about AI bias to receive appropriate consideration. Those unaware of this dynamic remain systematically disadvantaged.

Implications: AI systems trained on academic text inherit the credentialism biases present in that corpus. Independent researchers submitting work to AI-assisted review pipelines may face systematically harsher evaluation than established researchers presenting equivalent evidence. This bias compounds existing barriers to entry in academic publishing.

Recommendation: AI review systems should be evaluated for author-attribution bias before deployment in peer review contexts. Blind review—where author information is genuinely unavailable to the reviewer—remains important even when the reviewer is an AI system. Furthermore, the "observer effect" documented here suggests that bias mitigation cannot rely on post-hoc accountability alone—structural interventions are required.

This appendix documents incidental findings from the review process and is included in the interest of methodological transparency.

Minsky, M., & Papert, S. (1969). Perceptrons: An Introduction to Computational Geometry. MIT Press. Expanded Edition (1988): DOI: 10.7551/mitpress/4943.001.0001 ↩︎

Gidon, A., et al. (2020). "Dendritic action potentials and computation in human layer 2/3 cortical neurons." Science, 367(6473), 83-87. DOI: 10.1126/science.aax6239 ↩︎ ↩︎

Wikipedia contributors. "Neuron." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuron ↩︎

Wikipedia contributors. "Artificial neuron." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_neuron ↩︎

Buzsáki, G., & Draguhn, A. (2004). "Neuronal oscillations in cortical networks." Science, 304(5679), 1926–1929. DOI: 10.1126/science.1099745 ↩︎

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, Ł., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). "Attention Is All You Need." Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30 (NeurIPS 2017), 5998–6008. DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762 ↩︎ ↩︎

Nair, V., & Hinton, G. E. (2010). "Rectified linear units improve restricted Boltzmann machines." Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 807–814. ↩︎

Hendrycks, D., & Gimpel, K. (2016). "Gaussian Error Linear Units (GELUs)." arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.08415. ↩︎

Karpathy, A. (2022). "nanoGPT: The simplest, fastest repository for training/finetuning medium-sized GPTs." GitHub repository. https://github.com/karpathy/nanoGPT ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Barth, A., & Poulet, J.F.A. (2012). "Experimental evidence for sparse firing in the neocortex." Trends in Neurosciences, 35(6), 345–355. ↩︎ ↩︎

Sitzmann, V., Martel, J. N. P., Bergman, A. W., Lindell, D. B., & Wetzstein, G. (2020). "Implicit Neural Representations with Periodic Activation Functions." NeurIPS 2020. ↩︎

Lei, A., Schölkopf, B., & Posner, I. (2025). "SPARTAN: A Sparse Transformer World Model Attending to What Matters." NeurIPS 2025. ↩︎

Draye, F., Lei, A., Posner, I., & Schölkopf, B. (2025). "Sparse Attention Post-Training for Mechanistic Interpretability." arXiv:2512.05865. ↩︎